Reading Time: 3 minutes read

A short time ago, I was asked to write an article aimed at the local media about Donald Trump’s ‘fighting’ metaphors as they related to the January 6th attack on the US Capitol. I chose not to write that article, as I figured that Trump’s language on that day was anything but metaphorical. In my view, Trump incited a mob to riot and invade the Capitol building when he told his followers to march there and “fight like hell” while Congress was certifying Biden’s win. There was no figurative fighting involved.

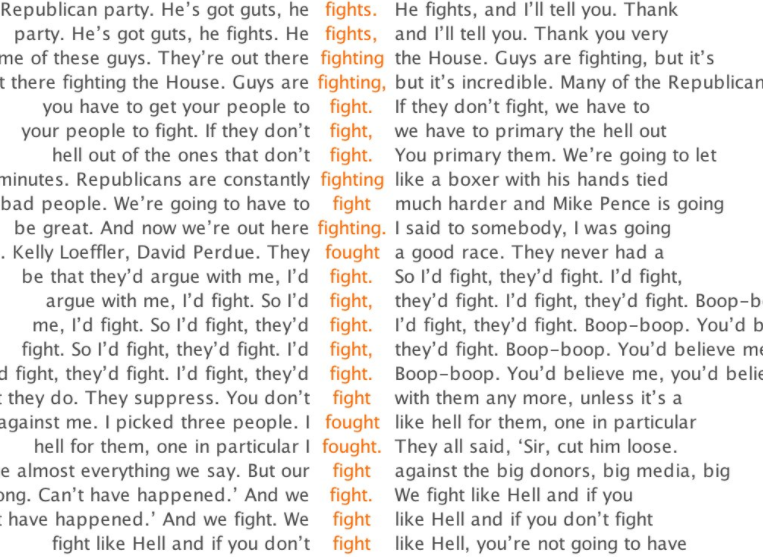

But Trump’s lawyers would have us believe that a literal interpretation of ‘fight’ in the context of his speech amounts to deliberately twisting the ex-president’s intention. Trump’s defense team explained that the then-president had “used the word ‘fight’ a little more than a handful of times and each time in the figurative sense”. They further claimed that “It was not and could not be construed to encourage acts of violence”.

Video evidence shows that that is not the case. Plenty of people were encouraged to commit acts of violence that day. Take a look and judge for yourself, here.

Anyone who followed Day 4 of the impeachment trial were treated to almost 10 minutes of an edited video showing various Democrats using the word ‘fight’ and other related terms. This video had been prepared by Trump’s defense team, intended to definitively demonstrate that figurative speech drawing upon the domain of war is standard issue in US public political discourse. But defense lawyer David Schoen forgave the Democrats for their use of this new f-word: “That’s okay. You didn’t do anything wrong, it’s a word people use, but please stop the hypocrisy.”

When interpreting metaphor (or indeed, any spoken or written discourse), context is crucial. That context includes not just the words one says, but also the situation in which they are said. No one is denying that politicians can, and do, employ ‘fighting’ words in a figurative sense in some of their addresses. And as linguist Elena Semino shows us, Trump’s speech on that January day also included many metaphorical instances of ‘fighting’:

As Semino notes, these figurative uses may make it easier for some to shift blame away from Trump — just as we have seen by his defense team.

But the President instructed an angry crowd to march on the Capitol, warning them “if you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore” — and all this after months spent convincing these same people that the election has been stolen and that their way of life is endangered. The accusation that the President incited a mob to violence does not stem from any sort of uncharitable or unwarranted interpretation, but rather from his words considered in the context in which they were uttered.

Just because most use of ‘fighting’ in political rhetoric is not literal does not mean that all such ‘fighting’ words are intended to be figurative. Any such implication is designed to mislead.

- For more about metaphor and inflammatory political rhetorical check out this earlier blog post: Metaphorical shooting.

- For more about Trump’s ‘fight like hell’ speech and metaphor, read Brigitte Nerlich’s blog post: Loaded language.

Storming of the Capitol image is free to share: CC BY-SA 4.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:DC_Capitol_Storming_IMG_7938.jpg